Listening to communities: Strengthening inclusivity & understanding

What is CPCS Listening Methodology and how is it carried out? How can listening projects be used in peacebuilding efforts to increase inclusivity and strengthen dialogue? What are the opportunities and challenges such an approach entails? How can listening methodology contribute to policy discussions to promote greater understanding and representation in peace processes?

The following is an extract from a new publication We Want Genuine Peace: Voices of communities from Myanmar’s ceasefire areas 2015, a major project carried out by CPCS based on 772 conversations carried out between November 2014 and March 2015 with 1,072 people living in six states which have ceasefires in Myanmar.

The Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS) recognises the importance of accessing the voices of communities to learn about how they have been affected, not only by ongoing conflict but also by the ongoing peace process.

Listening to the diverse voices of these communities and considering their experiences in the Myanmar peace process is crucial to finding solutions to address the long-standing problems that are at the heart of the violent conflicts. These voices also provide feedback to the negotiating parties on the positive and negative effects that the ongoing peace process is having on communities.

Listening Methodology

Listening Methodology

Listening Methodology is a qualitative, subject-oriented research approach used to analyse the direct experiences of individuals.

Listening research involves an inductive, comprehensive and systematic exploration of the ideas and insights of people living in and affected by a particular situation. It is used to identify key themes, trends, and common issues from a wide range of people, creating an opportunity to elevate voices that are less often heard and facilitating a channel to share opinions on a particular situation or plan for the future.

Listening origins & objectives

CDA-Collaborative Learning Development created the methodology to listen to communities receiving humanitarian aid. CPCS has been using Listening Methodology since 2009 in various locations across Asia to access less-heard voices in situations of violent conflict, post-conflict, and peace processes.

The methodology creates a collective voice by identifying main themes from the non-prescriptive conversations conducted with people with diverse viewpoints. By presenting these voices in publications, CPCS endeavours to support peace processes by contributing to policy discussions to promote inclusivity and representation in decision-making processes.

Listening as conflict transformation

Listening as conflict transformation

CPCS has also discovered that the process of listening creates transformational dialogue spaces by giving groups or actors in a conflict setting opportunities to interact with other groups, allowing them to widen their understanding of each other, transform relationships, and support the possibility for collaboration.

In this way, CPCS has used Listening Methodology as a conflict transformation tool. One challenge of gathering information in a conflict setting is people’s reluctance to share information. The use of conversations in Listening Methodology aims to overcome this challenge by creating a more relaxed environment where conversations can flow organically. This is crucial when working in conflict contexts, as participants who are engaged in more formal interview-based research have a tendency to censor their views.

The process also protects the anonymity of participants without compromising the integrity of the data by avoiding attributing statements directly to individuals. Instead, age, ethnicity, profession, town of residence, and other more general characteristics are used to describe participants.

Listening to the peace process

Listening to the peace process

In 2013, CPCS began to use Listening Methodology to support the Myanmar peace process. Listeners travelled to different parts of the country to have conversations with non-ranked or lower-ranking soldiers from six non-state armed groups (NSAGs) and the Myanmar Tatmadaw armed forces to hear their opinions, challenges, and desires for the future.

CPCS compiled these conversations into two publications (see links above) to

share them with a wider audience so they could be considered in the top-level

negotiation process.

In early 2014, another listening exercise was undertaken with a cross-section of community members living in Kayin (Karen) State to understand their opinions, experiences and desires for the future.

In early 2014, another listening exercise was undertaken with a cross-section of community members living in Kayin (Karen) State to understand their opinions, experiences and desires for the future.

Listening Methodology has also been used to elevate the voices of communities from six locations in Myanmar that experienced communal violence to share their first-hand perspectives about the violence that occurred. This project identified a strong alternative narrative that communal violence was not motivated by inter-religious animosity originating from within communities.

Listening to the ceasefires

Listening to the ceasefires

Recognising the need to elevate and monitor community perceptions and experiences of the Myanmar peace process, CPCS identified Listening Methodology as an appropriate and effective approach.

By accessing a cross-section demographic of community members living in states across Myanmar, themes detailing the most prevalent opinions, concerns and desires for the future of these populations are collected and distilled in a publication. The listening exercise is conducted every 12 months to enable these opinions to be monitored and compared for changes and consistency over time.

CPCS initially sought to conduct listening conversations in all ethnic states where various forms of peace agreements were being implemented (bilateral agreements, memoranda of understanding or  ceasefire agreements). However, only six areas were covered in the first year of implementation, namely: Kayin (Karen) State, Kayah State, Mon State, Kachin State, Northern Shan State and Southern Shan State.

ceasefire agreements). However, only six areas were covered in the first year of implementation, namely: Kayin (Karen) State, Kayah State, Mon State, Kachin State, Northern Shan State and Southern Shan State.

The decision to limit the scope to these areas was guided by time and funding considerations, as well as the availability of local partner organisations. The implementation of Listening Methodology requires the support of individuals who form listening teams.

With the help of local partners, individuals from target areas who are familiar with local contexts and had the ability to conduct conversations in the local language were invited to be listeners.

Methodology

CPCS connected with listeners by conducting a series of training workshops in state capitals to equip them with the necessary skills to carry out conversations with community members. These workshops focused on sharing the methodology, with exercises to orient participants in listening and bias mitigation techniques.

Listeners formed teams of two or three and travelled to various villages and townships in their respective states immediately following the training workshop. They were asked to speak with a cross-section of people living in these areas, who were recognised as relevant participants because they directly experience the effects of the peace process.

Listeners were given and asked to memorise a set of topic areas and guide questions to ensure consistency across conversations. They were instructed to try to cover all topic areas during these conversations, but were advised to be flexible and allow participants to discuss topics of their choosing. Conversations were conducted in the language that participants felt most comfortable speaking. Listeners were told not to take the guide questions with them or take notes during conversations.

Four tools were used to record data from the conversations: notebooks, logbooks, quote banks and, where possible, a photo diary. The details of each conversation were recorded in a notebook immediately after every conversation.

Each listener recorded a separate notebook, using his or her memory to identify the main themes and topics discussed. At the end of each day, listening teams met and discussed what they had heard over the course of multiple conversations. They used a logbook to record what they heard the most from all conversations that day. This daily debriefing and processing exercise acted as a preliminary stage of analysis for listeners to identify trends or patterns in the conversations.

Each listener recorded a separate notebook, using his or her memory to identify the main themes and topics discussed. At the end of each day, listening teams met and discussed what they had heard over the course of multiple conversations. They used a logbook to record what they heard the most from all conversations that day. This daily debriefing and processing exercise acted as a preliminary stage of analysis for listeners to identify trends or patterns in the conversations.

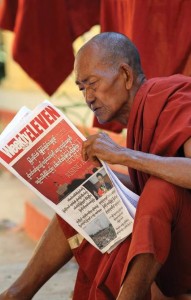

When listeners heard a phrase they felt captured the essence of a main point, they added it to a quote bank immediately after the conversations to capture quotations from participants that could be used as direct voices in the publication. A photo diary was also used for listeners to capture images from the locations of the conversations. Photos were meant to provide visual examples of the topics discussed in the conversations, such as road conditions or housing infrastructure.

After conducting conversations, listening teams reconvened for a two-day processing workshop facilitated by CPCS staff. Through a series of synthesis and analysis exercises, listeners identified the main overall themes in relation to each topic area/guide question, as well as differences and observations heard during conversations, to provide a snapshot of results in each state.

All materials used to record data (notebooks, logbooks and quotes) were translated from their original language to English for further analysis. To ensure that key themes, common issues and differences were accurately identified, CPCS went over the translated notebooks and logbooks and coded them into categories that were then compared to the main themes that listeners identified in the workshops.

The analysis found in this publication is based on the material written up from both stages. Quotations and detailed insights of participants were taken from the translated notebooks, logbooks, and quote banks to serve as direct and illustrative voices of community members.

Scope & limitations

Scope & limitations

Between November 2014 and March 2015, 772 conversations were carried out with 1,072 people. This exceeded the target number of 728 participants, which was calculated proportionally based on the size of each state population, using Kayah State (with a population of 300,000) as a baseline (80 participants).

The baseline figure was determined by taking into consideration the capacity of the research team as well as time constraints and full breakdown of participants, including ethnicity, age and gender can be found in the publication. The aim was to access participants who represent the diverse ethnic, gender, age, profession, and religious affiliations in each state.

In some cases, listening teams were not able to access a representative sample of some demographic groups. These inconsistencies are mentioned in the demographics section of each of the state chapters.

Countering bias

Countering bias

CPCS facilitators sought to address the issue of bias by conducting exercises during training workshops that taught listeners about self-awareness, perceptions and selection of participants.

Facilitators also identified bias in the primary data during the processing workshops by having in-depth discussions with listeners about the main themes and being aware of, or detecting, incongruent or inconsistent findings. After the processing workshops, facilitators also went through a guided reflection on the research process to identify listener bias, which they then noted during internal analysis and report writing.

Harnessing memory

Memory is an important component of Listening Methodology because it is assumed that listeners will most easily remember recurring themes from their conversations.

The daily debriefing sessions that listening teams held in the course of their work were designed to reinforce their memories. To preserve as much detailed information as possible, CPCS conducted processing workshops immediately after listeners had finished data collection.

During the processing workshops, listeners were asked to put away their notes and rely on their memories to identify the main themes that regularly emerged throughout the process. Giving listeners the space to compare and contrast their findings during the processing workshops also helps to stimulate their recollection of the main themes from their conversations.

Stimulating dialogue & inclusivity

Inclusivity and wide ownership are often hailed as the hallmarks of a robust and sustainable peace process. These are built by including communities, the people who will be directly affected by decisions made in the peace process, in the process.

But because the Myanmar peace process is largely a top-level process that concentrates on dialogue between the Myanmar Government, Tatmadaw and NSAG leadership, communities are usually left with little opportunity to engage with the process.

But because the Myanmar peace process is largely a top-level process that concentrates on dialogue between the Myanmar Government, Tatmadaw and NSAG leadership, communities are usually left with little opportunity to engage with the process.

Despite the direct impact the ongoing peace negotiations will have on their lives, communities often remain voiceless and invisible at the negotiating table.

CPCS chose to conduct conversations with community members from six different locations across Myanmar. These locations were chosen primarily because of the existing ceasefire agreements with the main NSAGs operating in these areas, as well as the presence of local partner organisations.

Using Listening Methodology to gather data, CPCS aims to produce a publication that can inform decision makers in the Myanmar peace process of the changing situation, needs and challenges for communities in states across Myanmar.

In creating this feedback mechanism, CPCS hopes to build inclusive engagement of all actors in the peace process and ensure local ownership and public support that is essential to sustainable and long-lasting peace.